|

Unboxing Everything:

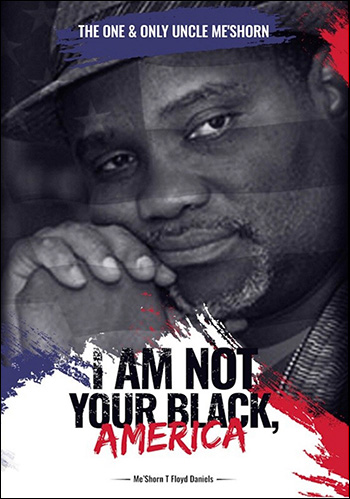

Interview with MeShorn Daniels

By Carin Chea

Describing up-and-coming author MeShorn Daniels can be challenging, as he is not one to be boxed in.

A retired Army veteran-turned-surgical technician, the writer’s debut book, I Am Not Your Black, America, reflects perhaps the singular thing that makes him stand out: His unrelenting refusal to be labeled.

And what a welcomed relief this is, especially as society continues to be flooded with influencers always encouraging us to find our “brand.”

Affectionately known as Uncle MeShorn, Daniels’ book is an unfiltered, passionate, and compelling letter to the country he grew up in and served. At a time fraught with political and racial tensions, Daniels’ memoir is a thought-provoking and relevant read.

Your nickname is Uncle MeShorn. How did that come about?

I’m 62-years-old, but I’m a big kid. It began because of the dynamics of my family. I was separated from my sister for over 20 years. In the process of finally connecting, I was married, my mother was living with me in Kentucky, and my sister was living in Atlanta.

My sister, at the time, had eight girls and one boy. Adam was the first child. When I went to meet them, they were all under the age of 15. She introduced me as Uncle MeShorn.

The first time I met them, we packed them up in my car and went to the store. They needed something? I made it rain. They wanted to go to the movies? I made it rain. When they got home, they wanted pizza, and bang! I took care of that.

One day, a few of them asked if they could live with us. My wife says, “Sure!” But, on that last day, I see 2 of my nieces with their luggage coming out. They were under ten. They said, “We’re coming with you! You said you could come to live with you and Uncle MeShorn.” I thought: “I didn’t mean right now.”

That’s how I realized that I am Uncle MeShorn who can make it rain.

I hope I don’t accidentally refer to you incorrectly. I understand you think the term “black American” or “black people” is a misnomer, yes? How would you label yourself?

I would label myself as an American of slaves.

Growing up, my parents did the best they could in the condition they were under. My grandfather (my mother’s father) looked white. Grand-daddy did not marry my grandmother for love.

My grand-daddy (who was born in Kentucky) actually selected my grandmother for the pigmentation of her skin, which was tar baby black. She was coal black. His parents were passing as white. He rejected what his parents were doing.

So he searched for a wife, not because of love, but because he wanted his children to have pigmentation in their skin. He had ten children, and had 8 miscarriages. My grandfather was trying to delineate his children.

When my mother’s father passed away, she stopped going to church and made a vow that if she had children, she would not introduce them to religion. Imagine a child like myself growing up, born in 1961, and it’s a traditional thing for black people to go to church. My whole childhood, we never went to church.

When I joined the military, I was a sheltered young man. In the military is where I started coming into my own.

Here I am, in the military with people who look like me, and they say to me, “You’re not black.” I said, “What do you mean?” They said I didn’t sound black, nor did I have the religious overtones.

The irony was – I wanted to learn how to be black. So, I started hanging out with people. Learning how to be black, took me down some dark, dark roads. I had to learn how to use profanities. I had to learn how to drink, do drugs, talk swagger, and have multiple women.

I had to learn these things to be associated and identified as black. My first 3 to 4 years, I was learning how to be black. By the end of that, I had it down.

There was something about me that older people saw in me that I didn’t see in myself. After all that effort in learning how to be down with the culture and black, my mentor, Perry Anderson, allowed me to stay with him after the military.

He was my adopted godfather. He allowed me to stay with him while on furlough. He told me: “Shorn, I want you to know. Your parents have done all they can do. This is your life now. You need to make the best of your military experience. What is it you’re coming back to? I think you ought to find something in the military you can do and you should go for it.”

My godfather was right. And, what was I most attracted to? Women. When I returned, I went into the medical field. That’s where all the women were. I changed my job from a cook into the medical field.

The counselor said to me: “I’m going to be honest with you. I don’t even know how you got to be a cook because you failed that aptitude test. You want to get into the medical field? You have to score a 91 and above. You scored under a 50. You should have been in the infantry.” And do you know why they suggested infantry?

No. Why?

Because they’re expendable. Bottom line: I had to re-educate and re-create myself. I scored over 91 when I took the test. When the recruiter came, I picked a surgical technologist.

Now, all this time, I have been learning how to be black. So, when I became a surgical technologist, they took me into the operating room for the first time, and nobody there looked like me.

The smell of the anesthetic and cleanliness, the cold air, it was overwhelming. The first case on the operating table? A total vaginal hysterectomy. I passed out. When I woke up, all these white people were laughing at me. They told me it was a normal thing.

I graduated, I became a surgical technologist, and in that dominant environment where no one else looked like me, I had learned how to navigate in that environment. The dominant European environment there, guess what they were telling me? “You’re not black! You don’t talk like it.”

Also, reading America’s Little Black Book by Dr. Norris Shelton was very impactful. He wrote that the demographics of people who came over to America were not negroes, blacks, or African Americans. They were Descendants of American Slaves.

From 1619 to 1865, that demographic of people formed from 15 original slave states, were creating slaves. When America transformed into America, they should’ve been called Descendants of American Slaves.

We should’ve never been identified as negroes, but as Descendants of American Slaves. I realized: I’m not black. I’m a Descendant of American slaves.

What was it that pushed you to write your first book? Tell us about I Am Not Your Black, America.

There were multiple incidents in my life. If you read the first two to three chapters, it will explain how I got there.

It was a process between coming into the military, reading Dr. Shelton’s book. I was in my second marriage, having two successful children, retired from the military and surgical technology.

In 2018, my wife and I moved from one community to another, and I was able to look at my retirement during the time of COVID. COVID led to me being able to think about writing my book. I had more free time to focus on the book.

When I discovered that I was not black, I went to where it all started, in Jamestown of 1619.

From that point in time to 2019, there were 400 years where those people were mis-labeled as black, negroes, and African American. That was an eye-opener. That’s biblical. They mention wandering for 400 years in the OId Testament.

So, when I realized that the 400-year anniversary was here, that got me started on writing the book.

What do you want your readers to take away from your book?

My book is not written for my demographic, for people who look like me. My demographic of people didn’t name themselves, but by the dominant culture.

I want my readers to know that I’m speaking to the dominant culture in my book. For our demographic of people to grow, we have to learn how to unlearn and relearn. We have to learn that we are not meant to be identified based on color. Our humanity matters.

Martin Luther King Jr. said: “We must lead by character and not by color.”

We didn’t name ourselves black, but the dominant European culture has the ability to take us out of this position.

If you could go back in time, what would you say to your younger self?

I was abused from the very beginning by my drunken uncle when I was in the crib. I often ask myself this same question and wonder: What would I change if I could go back in time?

I realized: I wouldn’t change a thing. I love myself. And you’re talking about someone who had low self-esteem growing up. I was suicidal. Hurt people hurt people.

My book has served as therapy for me. For me to say that today, I wouldn’t change anything? That’s growth.

For more information, please visit www.UncleMeShorn.com.

Home |

Actors/Models |

Art |

Books |

Dining

Film & Video |

Food & Wine |

Health & Fitness

MediaWatch |

Money and Business |

Music |

Profiles

Professional Services |

Sports |

Style & Fashion

Technology |

Theatre |

Travel & Leisure

Copyright 1995 - 2024 inmag.com

inmag.com (on line) and in Magazine (in print)

are published by in! communications, Inc.

www.inmag.com

|

Advertiser Info

Subscription Form

Contact Us

|